Home

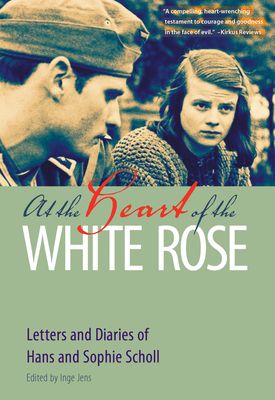

At the Heart of White Rose: Letters and Diaries Hans Sophie Scholl

Loading Inventory...

Barnes and Noble

At the Heart of White Rose: Letters and Diaries Hans Sophie Scholl

Current price: $20.00

Barnes and Noble

At the Heart of White Rose: Letters and Diaries Hans Sophie Scholl

Current price: $20.00

Loading Inventory...

Size: Paperback

*Product Information may vary - to confirm product availability, pricing, and additional information please contact Barnes and Noble

Personal letters and diaries provide an intimate view into the hearts and minds of a brother and sister who became martyrs in the anti-Nazi resistance during World War II.

Idealistic, serious, and sensible, Hans and Sophie Scholl joined the Hitler Youth

with youthful and romantic enthusiasm. But as Hitler’s grip throttled Germany and Nazi atrocities mounted, Hans and Sophie emerged from their adolescence with the conviction that at all costs they must raise their voices against the murderous Nazi regime.

In May of 1942, with Germany still winning the war, an improbable little band of students at Munich Universitybegan distributing the leaflets of the White Rose. In the very city where the Nazis got their start, they demanded resistance to Germany’s war efforts and confronted their readers with what they had learned of Hitler’s “final solution”: “Here we see the most terrible crime committed against the dignity of humankind, a crime that has no counterpart in human history.” These broadsides were secretly drafted and printed in a Munich basement by Hans Scholl, by now a young medical student and military conscript, and a handful of young co-conspirators that included his twenty-one-year-old sister Sophie. The leaflets placed the Scholls and their friends in mortal danger, and it wasn’t long before they were captured and executed.

As their letters and diaries reveal, the Scholls were not primarily motivated by political beliefs,

but rather came to their convictions through personal spiritual search that eventually led them to sacrifice their lives for what they believed was right. Interwoven with commentary on the progress of Hitler’s campaign, the letters and diary entries range from veiled messages about the course of a war they wanted their country to lose, to descriptions of hikes and skiing trips and meditations on Goethe, Dostoyevsky, Rilke, and Verlaine; from entreaties to their parents for books and sweets hard to get in wartime, to deeply humbled and troubled entreaties to God for an understanding of the presence of such great evil in the world. There are alarms when Hans is taken into military custody, when their father is jailed, and when their friends are wounded on the eastern front. But throughout—even to the end, when the Scholls’ sense of peril is most oppressive—there appear in their writings spontaneous outbursts of joy and gratitude for the gifts of nature, music, poetry, and art. In the midst of evil and degradation, theirs is a celebration of the spiritual and the humane.

Illustrated with photographs

of Hans and Sophie Scholl and their friends and co-conspirators.

Idealistic, serious, and sensible, Hans and Sophie Scholl joined the Hitler Youth

with youthful and romantic enthusiasm. But as Hitler’s grip throttled Germany and Nazi atrocities mounted, Hans and Sophie emerged from their adolescence with the conviction that at all costs they must raise their voices against the murderous Nazi regime.

In May of 1942, with Germany still winning the war, an improbable little band of students at Munich Universitybegan distributing the leaflets of the White Rose. In the very city where the Nazis got their start, they demanded resistance to Germany’s war efforts and confronted their readers with what they had learned of Hitler’s “final solution”: “Here we see the most terrible crime committed against the dignity of humankind, a crime that has no counterpart in human history.” These broadsides were secretly drafted and printed in a Munich basement by Hans Scholl, by now a young medical student and military conscript, and a handful of young co-conspirators that included his twenty-one-year-old sister Sophie. The leaflets placed the Scholls and their friends in mortal danger, and it wasn’t long before they were captured and executed.

As their letters and diaries reveal, the Scholls were not primarily motivated by political beliefs,

but rather came to their convictions through personal spiritual search that eventually led them to sacrifice their lives for what they believed was right. Interwoven with commentary on the progress of Hitler’s campaign, the letters and diary entries range from veiled messages about the course of a war they wanted their country to lose, to descriptions of hikes and skiing trips and meditations on Goethe, Dostoyevsky, Rilke, and Verlaine; from entreaties to their parents for books and sweets hard to get in wartime, to deeply humbled and troubled entreaties to God for an understanding of the presence of such great evil in the world. There are alarms when Hans is taken into military custody, when their father is jailed, and when their friends are wounded on the eastern front. But throughout—even to the end, when the Scholls’ sense of peril is most oppressive—there appear in their writings spontaneous outbursts of joy and gratitude for the gifts of nature, music, poetry, and art. In the midst of evil and degradation, theirs is a celebration of the spiritual and the humane.

Illustrated with photographs

of Hans and Sophie Scholl and their friends and co-conspirators.