Home

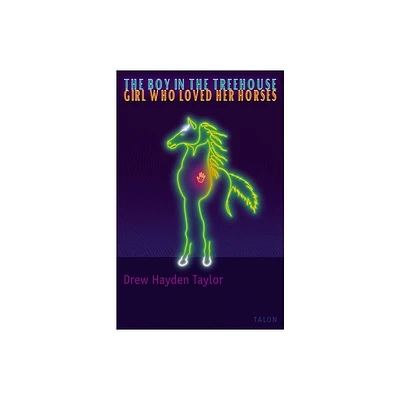

The Boy Treehouse / Girl Who Loved Her Horses

Loading Inventory...

Barnes and Noble

The Boy Treehouse / Girl Who Loved Her Horses

Current price: $18.95

Barnes and Noble

The Boy Treehouse / Girl Who Loved Her Horses

Current price: $18.95

Loading Inventory...

Size: Paperback

*Product Information may vary - to confirm product availability, pricing, and additional information please contact Barnes and Noble

In this collection of two plays about the process of children becoming adults, Drew Hayden Taylor works his delightfully comic and bitter-sweet magic on the denials, misunderstandings and preconceptions which persist between Native and Colonial culture in North America.

In “The Boy in the Treehouse,” Simon, the son of an Ojibway mother and a British father, climbs into his half-finished tree house on the vision-quest his books say is necessary for him to reclaim his mother’s culture. “It’s a Native thing,” he informs his incredulous father (who tells him he’d never heard of such a thing from his wife): “Only boys do it. It’s part of becoming a man.” Of course, what with the threats of the police, the temptation of the barbeque next door, and the distractions of a persistent neighbourhood girl, Simon probably wouldn’t recognize a vision if he fell over it.

“Girl Who Loved Her Horses” is the Native name for the strange and quiet Danielle from the non-status community across the tracks, imbued with the mysterious power to draw the horse “every human being on the planet wanted but could never have.” She is and remains an enigma to the people of the reservation, but the power of her spirit remains strong. Years later, a huge image of her horse reappears, covering an entire side of a building in a blighted urban landscape of beggars and broken dreams. The eyes of her stallion, which once gleamed exhilaration and freedom, now glare with defiance and anger. Danielle has clearly been forced to grow up.

With these two plays, Taylor rediscovers an issue long forgotten in our “post-historical” age: the nature of, and the necessity for, these rites of passage in all cultures.

In “The Boy in the Treehouse,” Simon, the son of an Ojibway mother and a British father, climbs into his half-finished tree house on the vision-quest his books say is necessary for him to reclaim his mother’s culture. “It’s a Native thing,” he informs his incredulous father (who tells him he’d never heard of such a thing from his wife): “Only boys do it. It’s part of becoming a man.” Of course, what with the threats of the police, the temptation of the barbeque next door, and the distractions of a persistent neighbourhood girl, Simon probably wouldn’t recognize a vision if he fell over it.

“Girl Who Loved Her Horses” is the Native name for the strange and quiet Danielle from the non-status community across the tracks, imbued with the mysterious power to draw the horse “every human being on the planet wanted but could never have.” She is and remains an enigma to the people of the reservation, but the power of her spirit remains strong. Years later, a huge image of her horse reappears, covering an entire side of a building in a blighted urban landscape of beggars and broken dreams. The eyes of her stallion, which once gleamed exhilaration and freedom, now glare with defiance and anger. Danielle has clearly been forced to grow up.

With these two plays, Taylor rediscovers an issue long forgotten in our “post-historical” age: the nature of, and the necessity for, these rites of passage in all cultures.