Home

The Woman behind the Lens: The Life and Work of Frances Benjamin Johnston, 1864-1952

Loading Inventory...

Barnes and Noble

The Woman behind the Lens: The Life and Work of Frances Benjamin Johnston, 1864-1952

Current price: $35.00

Barnes and Noble

The Woman behind the Lens: The Life and Work of Frances Benjamin Johnston, 1864-1952

Current price: $35.00

Loading Inventory...

Size: OS

*Product Information may vary - to confirm product availability, pricing, and additional information please contact Barnes and Noble

Try to picture Mark Twain, or Uncle Remus, or even Theodore Roosevelt. More than likely, you have a Frances Benjamin Johnston image in your mind. Johnston was a significant--and arresting--figure in early twentieth-century photography. Beautifully illustrated with forty examples of her work, this first full-length biography explores the surprising range of Johnston's talent, as well as her high-stepping, controversial character.

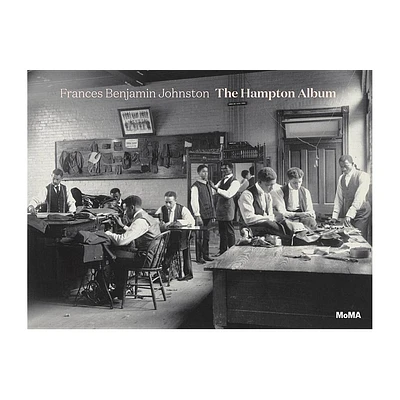

Johnston produced a good deal of the usual society portraiture of the time--including a nude photograph of a debutante that prompted the girl's outraged father to file a lawsuit--but she was also an important photodocumentarian. Students of African American history can reexamine life at Hampton Institute (now Hampton University) or Tuskegee using hundreds of photographs made by Johnston at the turn of the last century.

Through Johnston's work we can see Admiral Dewey on the deck of the USS Olympia, the Roosevelt children playing with their pet pony at the White House, and the gardens of Edith Wharton's famous villa near Paris. Johnston's major project on early vernacular architecture of the American South preserves scores of buildings that no longer exist except on her film.

However, while many are familiar with Johnston's photographs, most know little about the woman who made them. And without the context of her life, which Bettina Berch gives us in all its contradiction and color, Johnston's subjects may seem inchoate, her choices part feminist and part reactionary, part radical and part retrograde.

Johnston entered photography when the field was relatively new, and professional gender boundaries were still being defined. The invention of lighter equipment and changing technologies in developing meant that photography could be moved from the studio and darkroom--male provinces--out into the street or the home. But the repressiveness of late nineteenth-century society sometimes cast a shadow: there were a host of prescriptions governing proper female behavior, and certainly the sensuality of the human body as a subject caused many to argue that this new art form should remain a male preserve.

Within these boundaries, Johnston defined herself as an artist. Raised in an upper-middle-class household in Washington, D.C., she declined to "marry money" and instead made her living as an artist, although she enjoyed the cushion of her family's wealth and connections. In the course of her career, she moved through a series of interests, from portraiture to historic preservation. It is her restlessness, her resistance to easy categorizing, that makes this upper-class bohemian photographer such a fascinating subject herself.

Johnston produced a good deal of the usual society portraiture of the time--including a nude photograph of a debutante that prompted the girl's outraged father to file a lawsuit--but she was also an important photodocumentarian. Students of African American history can reexamine life at Hampton Institute (now Hampton University) or Tuskegee using hundreds of photographs made by Johnston at the turn of the last century.

Through Johnston's work we can see Admiral Dewey on the deck of the USS Olympia, the Roosevelt children playing with their pet pony at the White House, and the gardens of Edith Wharton's famous villa near Paris. Johnston's major project on early vernacular architecture of the American South preserves scores of buildings that no longer exist except on her film.

However, while many are familiar with Johnston's photographs, most know little about the woman who made them. And without the context of her life, which Bettina Berch gives us in all its contradiction and color, Johnston's subjects may seem inchoate, her choices part feminist and part reactionary, part radical and part retrograde.

Johnston entered photography when the field was relatively new, and professional gender boundaries were still being defined. The invention of lighter equipment and changing technologies in developing meant that photography could be moved from the studio and darkroom--male provinces--out into the street or the home. But the repressiveness of late nineteenth-century society sometimes cast a shadow: there were a host of prescriptions governing proper female behavior, and certainly the sensuality of the human body as a subject caused many to argue that this new art form should remain a male preserve.

Within these boundaries, Johnston defined herself as an artist. Raised in an upper-middle-class household in Washington, D.C., she declined to "marry money" and instead made her living as an artist, although she enjoyed the cushion of her family's wealth and connections. In the course of her career, she moved through a series of interests, from portraiture to historic preservation. It is her restlessness, her resistance to easy categorizing, that makes this upper-class bohemian photographer such a fascinating subject herself.